Lactoylglutathione lyase

| lactoylglutathione lyase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ribbon diagram of human glyoxalase I with its catalytic zinc ions shown as two purple spheres. An inhibitor, S-hexylglutathione, is shown as a space-filling model; the green, red, blue and yellow spheres correspond to carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and sulfur atoms, respectively. | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 4.4.1.5 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 9033-12-9 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

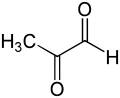

The enzyme lactoylglutathione lyase (EC 4.4.1.5, also known as glyoxalase I) catalyzes the isomerization of hemithioacetal adducts, which are formed in a spontaneous reaction between a glutathionyl group and aldehydes such as methylglyoxal.[1][2]

- (R)-S-lactoylglutathione = glutathione + 2-oxopropanal

Glyoxalase I derives its name from its catalysis of the first step in the glyoxalase system, a critical two-step detoxification system for methylglyoxal. Methylglyoxal is produced naturally as a byproduct of normal biochemistry, but is highly toxic, due to its chemical reactions with proteins, nucleic acids, and other cellular components. The second detoxification step, in which (R)-S-lactoylglutathione is split into glutathione and D-lactate, is carried out by glyoxalase II, a hydrolase. Unusually, these reactions carried out by the glyoxalase system does not oxidize glutathione, which usually acts as a redox coenzyme. Although aldose reductase can also detoxify methylglyoxal, the glyoxalase system is more efficient and seems to be the most important of these pathways. Glyoxalase I is an attractive target for the development of drugs to treat infections by some parasitic protozoa, and cancer. Several inhibitors of glyoxalase I have been identified, such as S-(N-hydroxy-N-methylcarbamoyl)glutathione.

Glyoxalase I is classified as a carbon-sulfur lyase although, strictly speaking, the enzyme does not form or break a carbon-sulfur bond. Rather, the enzyme shifts two hydrogen atoms from one carbon atom of the methylglyoxal to the adjacent carbon atom. In effect, the reaction is an intramolecular redox reaction; one carbon is oxidized whereas the other is reduced. The mechanism proceeds by subtracting and then adding protons, forming an enediolate intermediate, rather than by transferring hydrides. Unusually for a metalloprotein, this enzyme shows activity with several different metals. Glyoxalase I is also unusual in that it is stereospecific in the second half of its mechanism, but not in the first half. Structurally, the enzyme is a domain-swapped dimer in many species, although the two subunits have merged into a monomer in yeast, through gene duplication.

Nomenclature

[edit]The systematic name of this enzyme class is (R)-S-lactoylglutathione methylglyoxal-lyase (isomerizing; glutathione-forming); other names include:

- methylglyoxalase,

- aldoketomutase,

- ketone-aldehyde mutase, and

- (R)-S-lactoylglutathione methylglyoxal-lyase (isomerizing).

In some instances, the glutathionyl moiety may be supplied by trypanothione, the analog of glutathione in parasitic protozoa such as the trypanosomes. The human gene for this enzyme is called GLO1.

Gene

[edit]| GLO1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | GLO1, GLOD1, GLYI, HEL-S-74, glyoxalase I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 138750; MGI: 95742; HomoloGene: 4880; GeneCards: GLO1; OMA:GLO1 - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lactoylglutathione lyase in humans is encoded by the GLO1 gene.[7][8][9]

Structure

[edit]Several structures of glyoxalase I have been solved. Four structures of the human form have been published, with PDB accession codes 1BH5, 1FRO, 1QIN, and 1QIP. Five structures of the Escherichia coli form have been published, with accession codes 1FA5, 1FA6, 1FA7, 1FA8, and 1F9Z. Finally, one structure of the trypanothione-specific version from Leishmania major has been solved, 2C21. In all these cases, the quaternary structure of the biological unit is a domain-swapped dimer, in which the active site and the 8-stranded beta sheet secondary structure is formed from both subunits. However, in yeast such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the two subunits have fused into a single monomer of double size, through gene duplication. Each half of the structural dimer is a sandwich of 3-4 alpha helices on both sides of an 8-stranded antiparallel beta sheet; the dimer interface is largely composed of the face-to-face meeting of the two beta sheets.[1]

The tertiary and quaternary structures of glyoxalase I is similar to those of several other types of proteins. For example, glyoxalase I resembles several proteins that allow bacteria to resist antibiotics such as fosfomycin, bleomycin and mitomycin. Likewise, the unrelated enzymes methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase, 3-demethylubiquinone-9 3-O-methyltransferase and numerous dioxygenases such as biphenyl-2,3-diol 1,2-dioxygenase, catechol 2,3-dioxygenase, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetate 2,3-dioxygenase and 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase all resemble glyoxalase I in structure.[1] Finally, many proteins of unknown or uncertain function likewise resemble glyoxalase I, such as At5g48480 from the plant, Arabidopsis thaliana.

The active site has four major regions.

Function

[edit]

The principal physiological function of glyoxalase I is the detoxification of methylglyoxal, a reactive 2-oxoaldehyde that is cytostatic at low concentrations[10] and cytotoxic at millimolar concentrations.[11] Methylglyoxal is a by-product of normal biochemistry that is a carcinogen, a mutagen[12] and can chemically damage several components of the cell, such as proteins and nucleic acids.[11][13] Methylglyoxal is formed spontaneously from dihydroxyacetone phosphate, enzymatically by triosephosphate isomerase and methylglyoxal synthase, as also in the catabolism of threonine.[14]

To minimize the amount of toxic methylglyoxal and other reactive 2-oxoaldehydes, the glyoxalase system has evolved. The methylglyoxal reacts spontaneously with reduced glutathione (or its equivalent, trypanothione),[15]) forming a hemithioacetal. The glyoxalase system converts such compounds into D-lactate and restored the glutathione.[14] In this conversion, the two carbonyl carbons of the 2-oxoaldehyde are oxidized and reduced, respectively, the aldehyde being oxidized to a carboxylic acid and the acetal group being reduced to an alcohol. The glyoxalase system evolved very early in life's history and is found nearly universally through life-forms.

The glyoaxalase system consists of two enzymes, glyoxalase I and glyoxalase II. The former enzyme, described here, rearranges the hemithioacetal formed naturally by the attack of glutathione on methylglyoxal into the product. Glyoxalase II hydrolyzes the product to re-form the glutathione and produce D-lactate. Thus, glutathione acts unusually as a coenzyme and is required only in catalytic (i.e., very small) amounts; normally, glutathione acts instead as a redox couple in oxidation-reduction reactions.

The glyoxalase system has also been suggested to play a role in regulating cell growth[16] and in assembling microtubules.[17]

Properties

[edit]Glyoxalase I requires bound metal ions for catalysis.[18] The human enzyme[19] and its counterparts in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae)[20] and Pseudomonas putida[21] use divalent zinc, Zn2+. By contrast, the prokaryotic versions often use a nickel ion. The glyoxalase I found in eukaryotic trypanosomal parasites such as Leishmania major and Trypanosoma cruzi can also use nickel for activity,[15] possibly reflecting an acquisition of their GLO1 gene by horizontal gene transfer.[22]

A property of glyoxalase I is its lack of specificity for the catalytic metal ion. Most enzymes bind one particular type of metal, and their catalytic activity depends on having bound that metal. For example, oxidoreductases often use a specific metal ion such as iron, manganese or copper and will fail to function if their preferred metal ion is replaced, due to differences in the redox potential; thus, the ferrous superoxide dismutase cannot function if its catalytic iron is replaced by manganese, and vice versa. By contrast, although human glyoxalase I prefers to use divalent zinc, it is able to function with many other divalent metals, including magnesium, manganese, cobalt, nickel and even calcium.;[23] however, the enzyme is inactive with the ferrous cation.[24] Similarly, although the prokaryotic glyoxalase I prefers nickel, it is able to function with cobalt, manganese and cadmium; however, the enzyme is inert with bound zinc, due to a change in coordination geometry from octahedral to trigonal bipyramidal.[15] Structural and computational studies have revealed that the metal binds the two carbonyl oxygens of the methylglyoxal moiety at two of its coordination sites, stabilizing the enediolate anion intermediate.

Another unusual property of glyoxalase I is its inconsistent stereospecificity. The first step of its reaction mechanism (the abstraction of the proton from C1 and subsequent protonation of O2) is not stereospecific, and works equally well regardless of the initial chirality at C1 in the hemithioacetal substrate. The resulting enediolate intermediate is achiral, but the second step of the reaction mechanism (the abstraction of a proton from O1 and subsequent protonation of C2) is definitely stereospecific, producing only the (S) form of D-lactoylglutathione. This is believed to result from the two glutamates bound oppositely on the metal ion; either one is able to carry out the first step, but only one is able to carry out the second step. The reason from this asymmetry is not yet fully determined.

Reaction mechanism

[edit]The methylglyoxal molecule consists of two carbonyl groups flanked by a hydrogen atom and a methyl group. In the discussion below, these two carbonyl carbons will be denoted as C1 and C2, respectively. In both the hemithioacetal substrate and the (R)-S-lactoylglutathione product, the glutathione moiety is bonded to the C1 carbonyl group.

The basic mechanism of glyoxalase I is as follows. The substrate hemithioacetal is formed when a molecule of glutathione — probably in its reactive thiolate form — attacks the C1 carbonyl of methylglyoxal or a related compound, rendering that carbon tetravalent. This reaction occurs spontaneously in the cell, without the involvement of the enzyme. This hemithioacetal is then bound by the enzyme, which shifts a hydrogen from C1 to C2. The C2 carbonyl is reduced to a tetravalent alcohol form by the addition of two protons, whereas the C1 carbonyl is restored by losing a hydrogen while retaining its bond to the glutathione moiety.

A computational study, combined with the available experimental data, suggests the following atomic-resolution mechanism for glyoxalase I.[25] In the active site, the catalytic metal adopts an octahedral coordination geometry and, in the absence of substrate, binds two waters, two opposite glutamates, a histidine and one other sidechain, usually another histidine or glutamates. When the substrate enters the active site, the two waters are shed and the two carbonyl oxygens of the substrate are bound directly to the metal ion. The two opposing glutamates add and subtract protons from C1 and C2 and their respective oxygens, O1 and O2. The first half of the reaction transfers a proton from C1 to O2, whereas the second half transfers a proton from O1 to C2. The former reaction may be carried out by either of the opposing glutamates, depending on the initial chirality of C1 in the hemithioacetal substrate; however, the second half is stereospecific and is carried out by only one of the opposing glutamates.

It is worthy to note that the first theoretically confirmed mechanism for the R-substrate of glyoxalase one published recently.[26]

The catalytic mechanism of Glyoxalase have been studied by density functional theory, molecular dynamics simulations and hybrid QM/MM methods. The reason for the special specificity of the enzyme (it accepts both enantiomers of its chiral substrate but converts them to the same enantiomer of the product) is the higher basicity and flexibility of one of the active site glutamates (Glu172).[27][28][29]

Proton vs. hydride transfer

[edit]Glyoxalase I was originally believed to operate by the transfer of a hydride, which is a proton surrounded by two electrons (H–).[30] In this, it was thought to resemble the classic Cannizzaro reaction mechanism, in which the attack of a hydroxylate on an aldehyde renders it into a tetravalent alcohol anion; this anion donates its hydrogens to a second aldehyde, forming a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. (In effect, two identical aldehydes reduce and oxidize each other, leaving the net oxidation state the same.)

In glyoxalase I, such a hydride-transfer mechanism would work as follows. The attack of the glutathione would leave a charged O– and the aldehyde hydrogen bound to C1. If the carbonyl oxygen of C2 can secure a hydrogen from an obliging acidic sidechain of the enzyme, forming an alcohol, then the hydrogen of C1 might simultaneously slide over with its electrons onto C2 (the hydride transfer). At the same time, the extra electron on the oxygen of C1 could reform the double bond of the carbonyl, thus giving the final product.

An alternative (and ultimately correct) mechanism using proton (H+) transfer was put forward in the 1970s.[31] In this mechanism, a basic sidechain of the enzyme abstracts the aldehyde proton from C1; at the same time, the a proton is added to the oxygen of C2, thus forming a enediol. The ene means that a double bond has formed between C2 and C1, from the electrons left behind by the abstraction of the aldehyde proton; the diol refers to the fact that two alcohols have been made of the initial two carbonyl groups. In this mechanism, the intermediate forms the product by adding another proton to C2.

It was expected that solvent protons would contribute to forming the product from the enediol intermediate of the proton-transfer mechanism and when such contributions were not observed in tritiated water, 3H1O, the hydride-transfer mechanism was favored. However, an alternate hypothesis — that the enzyme active site was deeply buried away from water — could not be ruled out and ultimately proved to be correct. The first indications came when ever-increasing temperatures showed ever-increasing incorporation of tritium, which is consistent with proton transfer and unexpected by hydride transfer. The clinching evidence can with studies of the hydrogen-deuterium isotope effect on substrates fluorinated on the methyl group and deuterated on the aldehyde. The fluoride is a good leaving group; the hydride-transfer mechanism predicts less fluoride ion elimination with the deuterated sample, whereas the proton-transfer mechanism predicts more. Experiments on three types of glyoxalase I (yeast, rat and mouse forms) supported the proton-transfer mechanism in every case.[32] This mechanism was finally observed in crystal structures of glyoxalase I.

Clinical significance

[edit]Behavior

[edit]Glo1 expression is correlated with differences in anxiety-like behavior in mice[33][34] as well as behavior in the tail suspension test, which is sensitive to antidepressant drugs;[35] however, the direction of these effects have not always been consistent, which has raised skepticism.[36] Differences in Glo1 expression in mice appear to be caused by a copy number variant that is common among inbred strains of mice.[37] It has been proposed that the behavioral effects of Glo1 are due to the activity of its principal substrate methylglyoxal at GABAA receptors.[38] A small molecule inhibitor of glyoxalase I has been shown to have anxiolytic properties, thus identifying another possible indication for inhibitors of Glyoxalase I.[38]

As a drug target

[edit]Glyoxalase I is a target for the development of pharmaceuticals against bacteria, protozoans (especially Trypanosoma cruzi and the Leishmania) and human cancer.[39] Numerous inhibitors have been developed, most of which share the glutathione moiety. Among the most tightly binding family of inhibitors to the human enzyme are derivatives of S-(N-aryl-N-hydroxycarbamoyl)glutathione, most notably the p-bromophenyl derivative, which has a dissociation constant of 14 nM.[40] The closest analog of the transition state is believed to be S-(N-hydroxy-N-p-iodophenylcarbamoyl)glutathione; the crystal structure of this compound bound to the human enzyme has been solved to 2 Å resolution (PDB accession code 1QIN).[41]

Experiments suggest that methylglyoxal is preferentially toxic to proliferating cells, such as those in cancer.[42]

Recent research demonstrates that GLO1 expression is upregulated in various human malignant tumors including metastatic melanoma.[43][44]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Thornalley PJ (December 2003). "Glyoxalase I--structure, function and a critical role in the enzymatic defence against glycation". Biochemical Society Transactions. 31 (Pt 6): 1343–1348. doi:10.1042/BST0311343. PMID 14641060.

- ^ Farrera DO, Galligan JJ (October 2022). "The Human Glyoxalase Gene Family in Health and Disease". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 35 (10): 1766–1776. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.2c00182. PMC 10013676. PMID 36048613. S2CID 251978989.

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000124767 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000024026 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Ranganathan S, Walsh ES, Godwin AK, Tew KD (March 1993). "Cloning and characterization of human colon glyoxalase-I". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268 (8): 5661–7. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)53370-6. PMID 8449929.

- ^ Kim NS, Umezawa Y, Ohmura S, Kato S (May 1993). "Human glyoxalase I. cDNA cloning, expression, and sequence similarity to glyoxalase I from Pseudomonas putida". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268 (15): 11217–21. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)82113-5. PMID 7684374.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: GLO1 glyoxalase I".

- ^ Cameron AD, Olin B, Ridderström M, Mannervik B, Jones TA (June 1997). "Crystal structure of human glyoxalase I--evidence for gene duplication and 3D domain swapping". The EMBO Journal. 16 (12): 3386–95. doi:10.1093/emboj/16.12.3386. PMC 1169964. PMID 9218781.

- ^ a b Inoue Y, Kimura A (1995). "Unknown chapter title". In RK Poole (ed.). Advances in Microbial Physiology (volume 37 ed.). London: Academic Press. pp. 177–227.

- ^ Nagao M, Fujita Y, Wakabayashi K, Nukaya H, Kosuge T, Sugimura T (August 1986). "Mutagens in coffee and other beverages". Environmental Health Perspectives. 67: 89–91. doi:10.1289/ehp.866789. JSTOR 3430321. PMC 1474413. PMID 3757962.

- ^ Ferguson GP, Tötemeyer S, MacLean MJ, Booth IR (October 1998). "Methylglyoxal production in bacteria: suicide or survival?". Archives of Microbiology. 170 (4): 209–18. Bibcode:1998ArMic.170..209F. doi:10.1007/s002030050635. PMID 9732434. S2CID 21289561.

Oya T, Hattori N, Mizuno Y, Miyata S, Maeda S, Osawa T, et al. (June 1999). "Methylglyoxal modification of protein. Chemical and immunochemical characterization of methylglyoxal-arginine adducts". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (26): 18492–502. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.26.18492. PMID 10373458.

Thornalley PJ (1998). "Glutathione-dependent detoxification of α-oxoaldehydes by the glyoxalase system: involvement in disease mechanisms and antiproliferative activity of glyoxalase I inhibitors". Chem. Biol. Interact. 112–112: 137–151. Bibcode:1998CBI...111..137T. doi:10.1016/s0009-2797(97)00157-9. PMID 9679550. - ^ a b Thornalley PJ (1996). "Pharmacology of Methylglyoxal: Formation, Modification of Proteins and Nucleic Acids, and Enzymatic Detoxigfication — A Role in Pathogenesis and Antiproliferative Chemotherapy". Gen. Pharmac. 27 (4): 565–573. doi:10.1016/0306-3623(95)02054-3. PMID 8853285.

- ^ a b c Ariza A, Vickers TJ, Greig N, Armour KA, Dixon MJ, Eggleston IM, et al. (February 2006). "Specificity of the trypanothione-dependent Leishmania major glyoxalase I: structure and biochemical comparison with the human enzyme". Molecular Microbiology. 59 (4): 1239–48. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05022.x. PMID 16430697. S2CID 10113958.

- ^ Szent-Gyoergyi A (July 1965). "Cell-Division and Cancer". Science. 149 (3679): 34–7. Bibcode:1965Sci...149...34S. doi:10.1126/science.149.3679.34. PMID 14300523.

- ^ Gillespie E (January 1979). "Effects of S-lactoylglutathione and inhibitors of glyoxalase I on histamine release from human leukocytes". Nature. 277 (5692): 135–7. Bibcode:1979Natur.277..135G. doi:10.1038/277135a0. PMID 83539. S2CID 2153821.

- ^ Vander Jagt DL (1989). "Unknown chapter title". In D Dolphin, R Poulson, O Avramovic (eds.). Coenzymes and Cofactors VIII: Glutathione Part A. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- ^ Aronsson AC, Marmstål E, Mannervik B (April 1978). "Glyoxalase I, a zinc metalloenzyme of mammals and yeast". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 81 (4): 1235–40. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(78)91268-8. PMID 352355.

- ^ Ridderström M, Mannervik B (March 1996). "Optimized heterologous expression of the human zinc enzyme glyoxalase I". The Biochemical Journal. 314 (Pt 2): 463–7. doi:10.1042/bj3140463. PMC 1217073. PMID 8670058.

- ^ Saint-Jean AP, Phillips KR, Creighton DJ, Stone MJ (July 1998). "Active monomeric and dimeric forms of Pseudomonas putida glyoxalase I: evidence for 3D domain swapping". Biochemistry. 37 (29): 10345–53. doi:10.1021/bi980868q. PMID 9671502.

- ^ Greig N, Wyllie S, Vickers TJ, Fairlamb AH (December 2006). "Trypanothione-dependent glyoxalase I in Trypanosoma cruzi". The Biochemical Journal. 400 (2): 217–23. doi:10.1042/BJ20060882. PMC 1652828. PMID 16958620.

- ^ Sellin S, Eriksson LE, Aronsson AC, Mannervik B (February 1983). "Octahedral metal coordination in the active site of glyoxalase I as evidenced by the properties of Co(II)-glyoxalase I". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 258 (4): 2091–3. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)32886-2. PMID 6296126.

Sellin S, Mannervik B (1984). "Metal dissociation constants for glyoxalase I reconstituted with Zn2+, Co2+, Mn2+, and Mg2+". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 259 (18): 11426–11429. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)90878-1. PMID 6470005. - ^ Uotila L, Koivusalo M (April 1975). "Purification and properties of glyoxalase I from sheep liver". European Journal of Biochemistry. 52 (3): 493–503. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb04019.x. PMID 19241.

- ^ Himo F, Siegbahn PE (October 2001). "Catalytic mechanism of glyoxalase I: a theoretical study". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 123 (42): 10280–9. doi:10.1021/ja010715h. PMID 11603978.

- ^ Jafari S, Ryde U, Fouda AE, Alavi FS, Dong G, Irani M (February 2020). "Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics Study of the Reaction Mechanism of Glyoxalase I". Inorganic Chemistry. 59 (4): 2594–2603. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b03621. PMID 32011880. S2CID 211022551.

- ^ Jafari S, Ryde U, Irani M (September 2016). "Catalytic mechanism of human glyoxalase I studied by quantum-mechanical cluster calculations". Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic. 131: 18–30. doi:10.1016/j.molcatb.2016.05.010. S2CID 54031819.

- ^ Jafari S, Kazemi N, Ryde U, Irani M (May 2018). "Higher Flexibility of Glu-172 Explains the Unusual Stereospecificity of Glyoxalase I". Inorganic Chemistry. 57 (9): 4944–4958. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b03215. PMID 29634252.

- ^ Jafari S, Ryde U, Irani M (2019-01-01). "QM/MM study of the stereospecific proton exchange of glutathiohydroxyacetone by glyoxalase I". Results in Chemistry. 1: 100011. doi:10.1016/j.rechem.2019.100011.

- ^ Rose IA (July 1957). "Mechanism of the action of glyoxalase I". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 25 (1): 214–5. doi:10.1016/0006-3002(57)90453-5. PMID 13445752.

Franzen V (1956). "Wirkungsmechanismus der Glyoxalase I". Chemische Berichte/Recueil. 89 (4): 1020–1023. doi:10.1002/cber.19560890427.

Franzen V (1957). "Beziehungen zwischen Konstitution und katalytischer Aktivität der Thiolaminen bei der Katalyse der intramolekularen Cannizzaro-Reaktion". Chemische Berichte/Recueil. 90 (4): 623–633. doi:10.1002/cber.19570900427. - ^ Hall SS, Doweyko AM, Jordan F (November 1976). "Glyoxalase I enzyme studies. 2. Nuclear magnetic resonance evidence for an enediol-proton transfer mechanism". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 98 (23): 7460–1. doi:10.1021/ja00439a077. PMID 977876.

Hall SS, Doweyko AM, Jordan F (1978). "Glyoxalase I enzyme studies. 4. General base-catalyzed enediol proton-transfer rearrangement of methyl-glyoxalglutathionylhemithiol and phenylglyoxalglutathionylhemithiol acetal to S-lactoyl-glutathione and S-mandeloylglutathione followed by hydrolysis — Model for glyoxalase enzyme system". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 100 (18): 5934–5939. doi:10.1021/ja00486a054. - ^ Chari RV, Kozarich JW (October 1981). "Deuterium isotope effects on the product partitioning of fluoromethylglyoxal by glyoxalase I. Proof of a proton transfer mechanism". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 256 (19): 9785–8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)68690-4. PMID 7024272.

Kozarich JW, Chari RV, Wu JC, Lawrence TL (1981). "fluoromethylglyoxal - Synthesis and glyoxalase I catalyzed product partitioning via a presumed enediol intermediate". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 103 (15): 4593–4595. doi:10.1021/ja00405a057. - ^ Hovatta I, Tennant RS, Helton R, Marr RA, Singer O, Redwine JM, et al. (December 2005). "Glyoxalase 1 and glutathione reductase 1 regulate anxiety in mice". Nature. 438 (7068): 662–6. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..662H. doi:10.1038/nature04250. PMID 16244648. S2CID 4425579.

- ^ Krömer SA, Kessler MS, Milfay D, Birg IN, Bunck M, Czibere L, et al. (April 2005). "Identification of glyoxalase-I as a protein marker in a mouse model of extremes in trait anxiety". The Journal of Neuroscience. 25 (17): 4375–84. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0115-05.2005. PMC 6725100. PMID 15858064.

- ^ Benton CS, Miller BH, Skwerer S, Suzuki O, Schultz LE, Cameron MD, et al. (May 2012). "Evaluating genetic markers and neurobiochemical analytes for fluoxetine response using a panel of mouse inbred strains". Psychopharmacology. 221 (2): 297–315. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2574-z. PMC 3337404. PMID 22113448.

- ^ Thornalley PJ (May 2006). "Unease on the role of glyoxalase 1 in high-anxiety-related behaviour". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 12 (5): 195–9. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2006.03.004. PMID 16616641.

- ^ Williams R, Lim JE, Harr B, Wing C, Walters R, Distler MG, et al. (2009). "A common and unstable copy number variant is associated with differences in Glo1 expression and anxiety-like behavior". PLOS ONE. 4 (3): e4649. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4649W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004649. PMC 2650792. PMID 19266052.

- ^ a b Distler MG, Plant LD, Sokoloff G, Hawk AJ, Aneas I, Wuenschell GE, et al. (June 2012). "Glyoxalase 1 increases anxiety by reducing GABAA receptor agonist methylglyoxal". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 122 (6): 2306–15. doi:10.1172/JCI61319. PMC 3366407. PMID 22585572.

- ^ Thornalley PJ (1993). "The glyoxalase system in health and disease". Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 14 (4): 287–371. doi:10.1016/0098-2997(93)90002-U. PMID 8277832. S2CID 45479697.

- ^ Murthy NS, Bakeris T, Kavarana MJ, Hamilton DS, Lan Y, Creighton DJ (July 1994). "S-(N-aryl-N-hydroxycarbamoyl)glutathione derivatives are tight-binding inhibitors of glyoxalase I and slow substrates for glyoxalase II". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 37 (14): 2161–6. doi:10.1021/jm00040a007. PMID 8035422.

- ^ Cameron AD, Ridderström M, Olin B, Kavarana MJ, Creighton DJ, Mannervik B (October 1999). "Reaction mechanism of glyoxalase I explored by an X-ray crystallographic analysis of the human enzyme in complex with a transition state analogue". Biochemistry. 38 (41): 13480–90. doi:10.1021/bi990696c. PMID 10521255.

- ^ Együd LG, Szent-Györgyi A (June 1968). "Cancerostatic action of methylglyoxal". Science. 160 (3832): 1140. Bibcode:1968Sci...160.1140E. doi:10.1126/science.160.3832.1140. PMID 5647441.

Ayoub FM, Allen RE, Thornalley PJ (May 1993). "Inhibition of proliferation of human leukaemia 60 cells by methylglyoxal in vitro". Leukemia Research. 17 (5): 397–401. doi:10.1016/0145-2126(93)90094-2. PMID 8501967. - ^ Bair WB, Cabello CM, Uchida K, Bause AS, Wondrak GT (April 2010). "GLO1 overexpression in human malignant melanoma". Melanoma Research. 20 (2): 85–96. doi:10.1097/CMR.0b013e3283364903. PMC 2891514. PMID 20093988.

- ^ Santarius T, Bignell GR, Greenman CD, Widaa S, Chen L, Mahoney CL, et al. (August 2010). "GLO1-A novel amplified gene in human cancer". Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer. 49 (8): 711–25. doi:10.1002/gcc.20784. PMC 3398139. PMID 20544845.

Further reading

[edit]- Ekwall K, Mannervik B (February 1973). "The stereochemical configuration of the lactoyl group of S-lactoylglutathionine formed by the action of glyoxalase I from porcine erythrocytes and yeast". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 297 (2): 297–9. doi:10.1016/0304-4165(73)90076-7. PMID 4574550.

- Racker E (June 1951). "The mechanism of action of glyoxalase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 190 (2): 685–96. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)56017-8. PMID 14841219.

- Allen RE, Lo TW, Thornalley PJ (April 1993). "A simplified method for the purification of human red blood cell glyoxalase. I. Characteristics, immunoblotting, and inhibitor studies". Journal of Protein Chemistry. 12 (2): 111–9. doi:10.1007/BF01026032. PMID 8489699. S2CID 31587421.

- Larsen K, Aronsson AC, Marmstål E, Mannervik B (1985). "Immunological comparison of glyoxalase I from yeast and mammals and quantitative determination of the enzyme in human tissues by radioimmunoassay". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. B, Comparative Biochemistry. 82 (4): 625–38. doi:10.1016/0305-0491(85)90499-7. PMID 3937656.

- Vander Jagt DL, Daub E, Krohn JA, Han LP (August 1975). "Effects of pH and thiols on the kinetics of yeast glyoxalase I. An evaluation of the random pathway mechanism". Biochemistry. 14 (16): 3669–75. doi:10.1021/bi00687a024. PMID 240387.

- Phillips SA, Thornalley PJ (February 1993). "The formation of methylglyoxal from triose phosphates. Investigation using a specific assay for methylglyoxal". European Journal of Biochemistry. 212 (1): 101–5. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17638.x. PMID 8444148.